By Erin Fee, Staff Writer and Researcher for Save The Water™ | June 10, 2019

A 2019 study of waterways in 10 European countries is a reminder of how pesticides pollute our water worldwide. Scientists from Greenpeace Research Laboratories tested waterways in Austria, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and the United Kingdom. The scientists found 103 types of pesticide in Europe’s rivers and canals, 24 of which are banned by the European Union. Also, of the 29 waterways tested, 13 had a pesticide concentration above the acceptable level.1 In light of this information, this article provides a quick overview of the basics of pesticide pollution: what, where, why, and how.

A single body of water can contain a huge variety of pesticides. So we may know how an individual pesticide affects human and environmental health. But what happens when several types of pesticides are mixed together in a body of water? This is one of the reasons why pesticide pollution is such a challenging—and important—issue.

What Are Pesticides?

Pesticides are substances that control pests. Pests can be rodents, insects, weeds, bacteria, fungi, or any other unwanted organism.2 If you have ever applied bug spray or used a weed killer, then you have used a pesticide. Also, farmers use enormous amounts of pesticide to protect crops.

Why Are Pesticides In Our Water?

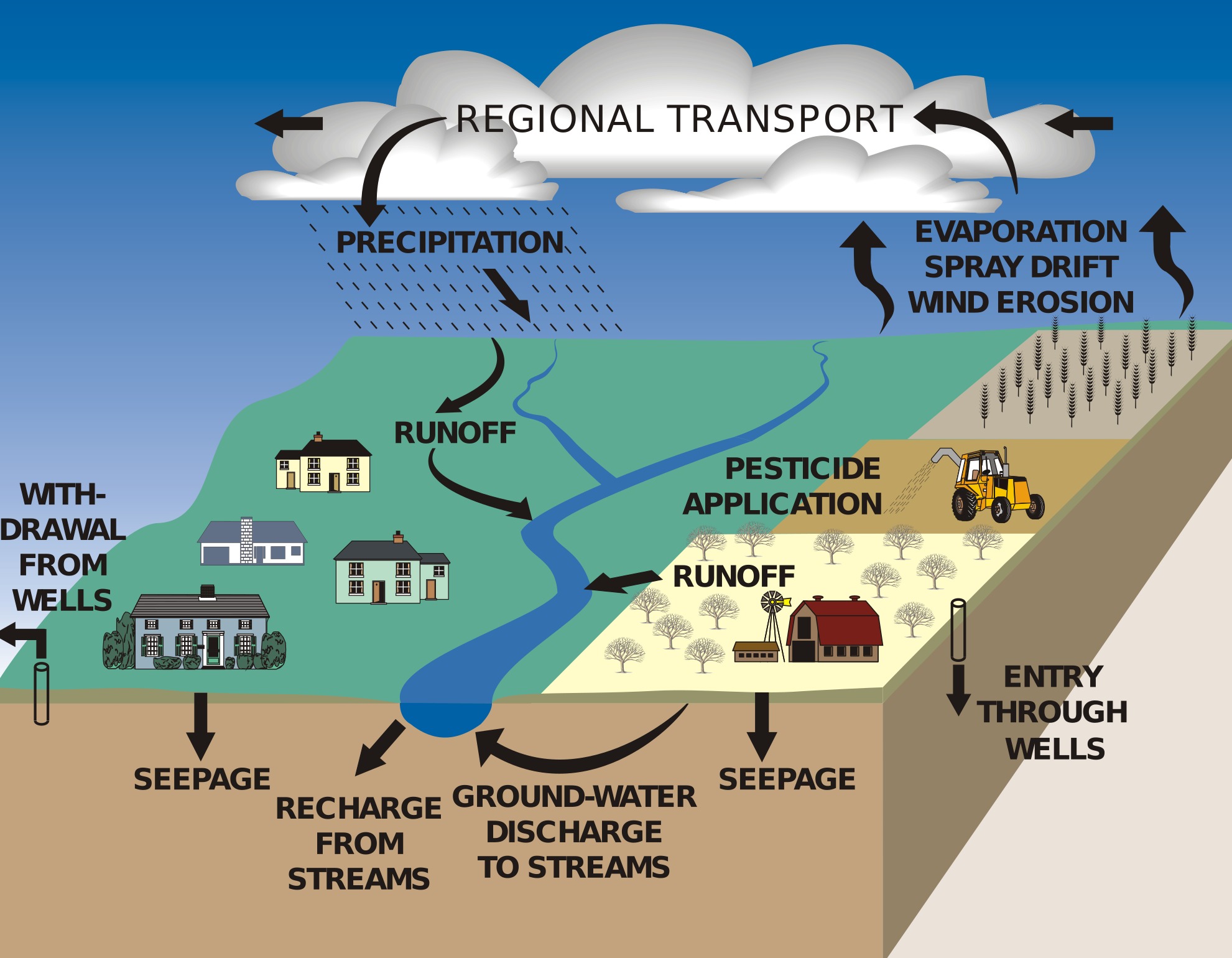

People dump some types of pesticides directly into waterways to control aquatic weeds and animals.2 However, people are directed to keep those substances away from drinking water sources. That being said, dangerous pesticides can easily spread out of control. For pesticides sprayed on agricultural fields, over 98 percent of insecticides (targeting unwanted insects) and 95 percent of herbicides (targeting unwanted plants) reach somewhere other than their target species.3

Picture this: a pesticide is sprayed on crops. But before the pesticide binds to the plants, rain washes it away. Some of the water, now polluted with pesticide, flows into lakes and rivers. While there, the pesticide disrupts the aquatic ecosystems. Which is to say, instead of killing weeds in a farming field, the pesticide kills or poisons life-giving plants underwater.

In addition, water with pesticide in it seeps into the soil. As a result it joins our supply of groundwater, an important source of drinking water. Also, if the water with pesticide in it enters a private well, people probably won’t test or treat it before using it.2

When the water with pesticides in it evaporates, the water becomes a part of the hydrologic cycle. The hydrologic cycle describes how water evaporates into vapor, condenses into clouds, and returns to the earth as rainfall or snow.4 Therefore, pesticides can spread great distances during this cycle.

How Toxic Are Pesticides?

Needless to say, there is a big difference between drinking water with very, very small (also called “trace”) amounts of pesticide and being sprayed directly in the face with weed killer. There are many kinds of pesticides. To be sure, each differs in its type and level of toxicity (Save The Water™ writer April Day has written about pesticides that disrupt how the human body works here). Toxicity is the level of being poisonous.5 Additional considerations include how concentrated the pesticide is, how long someone has been drinking the polluted water, and how other pollutants react with the pesticide.2

Though the exact health effects of drinking water with pesticide in it vary from case to case, the potential for toxicity is always there. Scientists have observed long-term effects such as cancer, organ damage, and reproductive issues.2

What Can You Do About Pesticide Pollution?

You can take steps to minimize your personal impact on pesticide pollution:5

- Firstly, read and follow directions carefully when using pesticides.

- Avoid sprays with a smaller droplet size, as it will spread more easily.

- Check the weather forecast. Wait to use the pesticide if the forecast projects rain or heavy winds.

- Clean pesticide equipment away from waterways or storm drains.

- Consider using non-toxic methods to control pests.

References

- University of Exeter. April 8, 2019. “Banned pesticides in Europe’s rivers.” ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/04/190408114243.htm

- National Pesticide Telecommunications Network. July 2000. “Pesticides in drinking water.” NPIC. http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/drinkingwater.pdf

- Amber Pariona. April 25, 2017. “The environmental impact of pesticides.” World Atlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-is-the-environmental-impact-of-pesticides.html

- Northwest River Forecast Center. n.d. “Description of hydrologic cycle. NOAA. https://www.nwrfc.noaa.gov/info/water_cycle/hydrology.cgi

- “Toxicity.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/toxicity

National Pesticide Information Center. April 15, 2019. “Pesticides and water resources.” http://npic.orst.edu/envir/waterenv.html